Courtesy, Brookline Preservation Commission

The Sewall House serves as a good introduction to the various architectural styles of Brookline. This house is typical of the Federal style, four-square (four equal sides) with a symmetrical facade and a hip roofline. Although the building has undergone many alterations through the years, its former elegance still shows in its handsome lines.

Passing Wellington Terrace and continuing down Cypress Street toward the center of the Point neighborhood, one can see the line-up of triple-deckers along Mulford and Edwin streets. The development of three-deckers is the most significant architectural motif in the Point since this was the prevalent housing form at the turn of the century. Practical, solidly built structures, three-deckers are typically characterized by high ceilings, large rooms, and ample window lighting. There has been increasingly wide recognition of their value both as a housing type and as an architectural statement of a particular period in our history. Although the ornamental details of the three-decker generally are sparser than those of the single-family house of the Victorian era, they are well worth retaining. These details reflect a standard of craftmanship which would be costly, if not prohibitive, today.

Cornice trim and moldings, projecting bay windows, and elaborate bracketing along windows, doors, and rooflines, provide a sense of individuality to these buildings and a visual richness to the surrounding streetscape. [2] For instance, the three-decker at the corner of Mulford and Cypress has decorative entablatures with a swag motif over several of the windows [Editor's note: eliminated after renovations]. In addition, the gable roof pediment provides emphasis to the three-story bay windows by 'capping' them. [3] Similarly, the flat-roofed structure at 6 Edwin Street built several years later has pleasant architectural detailing--dentils along the cornice as well as the three-story porches with fluted columns and simple balusters. When these houses on Mulford and Edwin streets were built in the late nineteenth century, Harriet Vass' greenhouses and homestead were sited on the current Clark Playground. These 'hothouses' were a thriving enterprise for at least two residents of the Point. The Quinn greenhouses, originally sited near the corner of Franklin and Chestnut streets, were relocated near the Vass' operations by 1900. In fact, looking west from the end of Edwin Street, one can see a large gable roof structure, once owned by the Quinn family. Built circa 1854 this house was part of the Charles Goddard estate which was bought by James Quinn around the turn of the century. Shortly thereafter Quinn erected the greenhouses and subdivided the portion of land running along Chestnut Street down to Kendall Street to enable the residential development of the area.[5] Before leaving this street, take note of the cottage at 16 Edwin Street. This small dwelling is decorated by bracketing, finial and pendant details in the gable, Queen Anne spindles on the front porch, and a wide bargeboard with a bull's-eye motif [Editor's note: altered or eliminated after renovations]. Although accounts are sketchy, it apparently was moved to this site in the early twentieth century, either from the immediate vicinity or the Coolidge Corner area. [6] As one approaches the intersection of Cypress, Kendall, and Rice streets, the Town Garage--formerly the Town Stables--comes into view. Although the presence of fencing, gasoline pumps, and other twentieth century additions obscure the lines of the building, its architecture deserves attention. The right side of the building, constructed in 1874, was designed by Charles K. Kirby, a well-known Boston architect. The vertical boarding and gabled window which pierces the second story roofline give a slightly Gothic flavor to this older section. Like 16 Edwin Street, noted previously, this too has bargeboard with a bull's-eye motif and stick work bracketing with a dropped pendant.

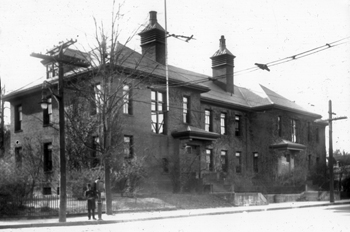

Several decades later, in 1898, the Town appropriated monies to 'enlarge and reconstruct the Town Stables at a cost not exceeding $25,000'. Peabody and Stearns, a nationally important Boston architectural firm of the time, was commissioned to prepare the design for the expanded facility for a fee of $752.00. The details incorporated in the final stable plans were features used in their designs for many of the area's finer residences. The projecting central gable with its return cornice and denti1s has a fanlight with radiating voussoirs and brick keystone as a central focus. The windows and entrances to this newer section carry a similar design. [7] 0n the left is Hart Street, one of the few streets in the Point which still carries its original name. It has an interesting history dating to the mid-1800s. Captain Benjamin Bradley, who lived up on Bradley's Hill (where Clark and Philbrick roads are today), built a heterogeneous collection of small frame houses. After his death in 1856, the properties remained on Bradley's Hill until 1871 when the houses were bought by Mr. Hart and moved to Hart Street, or 'Hart's Content' as it was then called. When the residents from Bradley's Hill moved to this new location, they were joined by another group of residents from. Pearl Street. These attractive houses still stand today forming a close-knit community with their picket fences, steep gable roof1ines, and diminutive scale. [8] Farther down Cypress Street at the corner of Franklin Street stands the Sewall School. This structure, built in 1892 along the lines of the earlier Winthrop School (now Lynch Recreation Center) on Brookline Avenue, was designed by the architectural firm of Cabot, Everett, and Mead. One of the most salient features Sewall School of the building is the stepped copper flashing along the entrance hoods and chimneys. The original slate on the hip roof, the brownstone lintels and sills, and sculptured bracketing of the entrance contribute to the richness of this brick edifice.

Turning left onto Franklin Street from Cypress, one sees Robinson Playground to the right which was formerly the site of the old Boston Elevator Railway Yard. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the trolleys which ran down Cypress Street terminated here. Once the bustling site of railroad activity, it is now a much-used recreation area. Continuing around the curve on Franklin Street, the cluster of Victorian era housing on the left strikes a sharp contrast with the much newer housing on the right.

[9] Before passing Rice Street note the rhythm created by the repetitive features of the entranceways at numbers 6,8, and 10. Whereas 10 Rice Street has elaborate cut-out bracketing and pendants, the other entrances have simpler, sculptured detailing. [10] Near the corner of Franklin and Rice streets are several flat-roofed triple-deckers which have dentils reflecting the revived interest in classical architecture during the 1910s and 1920s. This influence can be seen in the heavy fluted porch columns, the square posted balustrades, and the wide friezes. [11] Farther on the left, one can look down Vogel Place and see a small, intimate grouping of four early twentieth century residences. Characterized by gable rooflines, symmetrical fenestration, bracketed entrance hoods, and fieldstone foundations, each house is basically a replica of its neighbors. [12] Across the street at 32 and 28 Oakland Road stand two houses built around the turn of the century. Influences of the Shingle style can be seen in the low, horizontal orientation of the buildings, the prominent gambrel rooflines, the shed dormers, and the surface material. Also common to the Shingle style is the low veranda with massive columns. While decorative ornamentation tended to be minimal with Shingle style houses, classical influences can be seen in the decorative treatment, particularly the detailing beneath the window sills, the imitation leaded glass of the first-floor windows, and the tracery in the entrance sidelights. [13] Though built in 1904 by Everett and Mead, 19 Oakland Road recreates detai1ing of the Greek Revival period evident in the wide corner boards, the off-center entrance with flat pilasters and simple entablature, and the pedimented gable facing the street. [14] Before one leaves Oakland Road, mention should be made of Albert A. Cobb, a prominent Boston merchant engaged in the East India trade, who made his home on this street. The Cobb family, which had large land holdings in the immediate area, held on to this land for years, thus slowing the development of this portion of the Point. The house at 22 Oakland Road, built in the mid-nineteenth century, was the Cobb homestead.1 This building, which initially stood closer to Walnut Street, was moved back to its present site in 1903. Italianate influences are apparent in the elongated 2/2 windows, the entrance, the narrow corner boards, and the steep gable with return cornice. Set behind the Cobb house is the former carriage house, a plain clapboard structure with a gable roof. [15] In striking contrast to the simple Cobb homestead are the grand stone edifices on Walnut Street, the last stop on this walking tour. At the time they were built for Mr. Cobb in 1887-88, Walnut Terrace circled in front of these stately buildings. When Oakland Road was cut through in 1905, however, Walnut Terrace was eliminated. The medieval architectural richness of these buildings cannot be overstated. Characteristic of this style are huge chimneys, projecting two-story bays, irregular fenestration and multiple roofs with contrasting surface materials. Heavy Romanesque segmental arches mark the dominant entrances and windows. Used for the window lintels and sills, sandstone similarly defines the quoining at the buildings' edges and the stepped gable roof. Copper flashing used a long the cornice, dormers and chimneys provides additional textural richness by highlighting these elements and the profiles of the buildings.© 1986, 1996 Brookline Preservation Commission. All rights reserved.

Originally prepared and printed in 1986 by Carla Benka, Greer Hardwicke, and Leslie Larson, edited and reformated in 1996 by Roger Reed and Greer Hardwicke, funded through the Community Development Block Grant Program of the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

© 2020 Brookline Historical Society