PROCEEDINGS

OF THE

BROOKLINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

AT THE

ANNUAL MEETING, JANUARY 19, 1910

BROOKLINE, MASS.

PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY

MCMX

OF THE

BROOKLINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

AT THE

ANNUAL MEETING, JANUARY 19, 1910

BROOKLINE, MASS.

PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY

MCMX

BROOKLINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

NINTH ANNUAL MEETING.

NINTH ANNUAL MEETING.

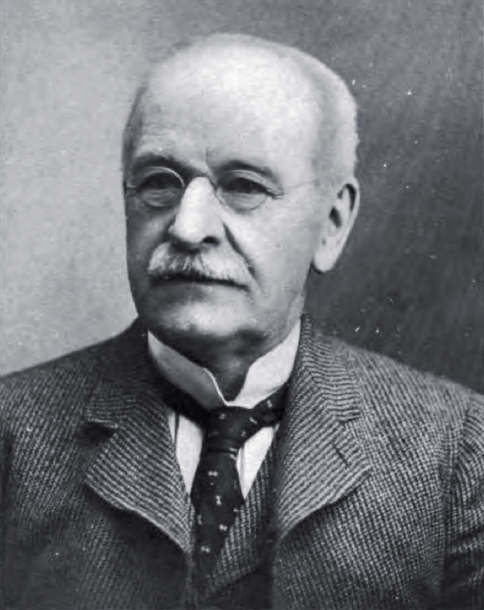

George Sumner Mann

A paper read before the Brookline Historical Society November 25, 1908, by George S. Mann.

Not only at the present time, but in the past, history has recorded the deeds of political actors and statesmen a number of whom in our own country, especially in provincial and in colonial times, have made their impress upon us by their strenuousness, oddity and boldness of action-such as "John Randolph of Roanoke," for an extreme example.

Could the glaring inconsistencies and illogical deeds recorded of some of these historical characters be erased from the pages of history how much more it would add to their reputation as statesmen. But as this cannot be done it may be of some consolation to know that in this world of transitory existence men are not altogether perfect. Nevertheless, in our enlightened age we have more mature and keener intellects than in ye olden time when many of the inhabitants are said to have been in such a low state of intelligence as to be accounted by an early historian well-nigh "social animals."

In the formation of our government out of the old colonial system we were extremely fortunate in having many able and patriotic statesmen whose difficult task was to harmonize the various and conflicting interests represented by the thirteen independent states and consolidate them into a general government, by a legal compact known as our Federal Constitution.

To be a little more definite in my subject-matter, I will name Gouverneur Morris, as my text, an American citizen, who took an active part in the affairs of government of that period. At the outset let me say that in a paper of thirty or forty minutes, one can mention only a few of the important events, and these briefly, in the strenuous life of this statesman whose unique and somewhat erratic career covered a period of forty-five years.

Gouverneur Morris was born in the family's manor-house at Morrisania, New York, January 31, 1752, and on the estate where his forefathers had dwelt for three generations. By birth he was an aristocrat. His great-grandfather, Richard Morris, who had served under Cromwell, came to the lower Hudson and settled in Westchester County, bordering on Haerlem River, where he purchased a vast estate, a manorial grant, known more than two hundred years ago by its present designation, "Morrisania"-then almost wholly a natural forest-now the upper part of New York City. Lewis Morris, son of the original proprietor, was left an orphan. He was an impetuous youth and wandered to the West Indies, but returned and took an active part in the colonial administration. He became Chief Justice of New York and died while governor of New Jersey. This was the grandfather of Gouvemeur Morris. Lewis Morris, Jr. (son of Gouverneur's grandfather) was also in public life. His brother, Robert Hunter Morris, was for a time governor of Pennsylvania. "In my Journey to Boston this year 1754," writes Franklin, "I met at New York with our new Governor, Mr. Morris, just arrived there from England, with whom I had been before intimately acquainted." He was called a disputatious official. The fourth son of his elder brother Lewis is the subject of this paper. Gouverneur's father died early, having directed in his will that his son Gouverneur "should have the best education that is to be had in England or America." Both the father and grandfather of Gouverneur for a period had occupied the bench.

The Morrises had the reputation of being of restless dispositions, of strong intellects, eccentric and erratic tempers. Young Gouverneur inherited also many of the vivacious traits of the French, for his mother was one of the Huguenot Gouverneurs who settled in New York after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. He was a boy of active parts and fond of out-door sports. He was early put to school in the family of a French teacher at New Rochelle, where he also took a rapid course of instruction in the classics. The church services there being often held in French he learned to speak and write that language nearly as well as he could in English.

From thence he entered King's College (now Columbia), where we find him a graduate at the early age of sixteen. It is said that Latin and mathematics were his favorite studies. He must have profited by the course, for his Commencement exercise on "Wit and Beauty" and his subsequent "Master of Arts" theme on "Love" were treated with considerable ingenuity and were enthusiastically applauded by the young ladies, many of whom, no doubt, were attracted to him, for he was a tall, handsome young man with finely cut features, and graceful in his bearing. He studied law with a man of celebrity in the Colony, William Smith, a Chief Justice, and author of the History of the Province. While a student young Morris attracted some attention by his writings against a financial project of the Assembly, and before he was twenty was a full-fledged Attorney at Law. He was licensed to practise in the Courts in 1771, tho' I failed to find evidence that he made any considerable use of his profession at the New York bar thus early. Among the very few cases he tried was one concerning a contested election, in which he was pitted against John Jay. About this time, in a letter to his friend Judge William Smith, asking advice about visiting Europe, he says, "I desire this trip to form my manners and address by the example of the truly polite, to rub off in the gay circle a few of the many barbarisms which characterize a provincial education." He obeyed the injunction of his old preceptor, however, who said to him, "Imitate your grandfather who stayed in America and prospered rather than spend a fortune abroad in imitation of one of your uncles." He now turned his attention to the affairs in the Colony which were much unsettled.

Early development and responsibility were marked traits of our Revolutionary worthies. The habit of forming opinions and resolutely maintaining them was a characteristic of the Morris family. There was a great opportunity for the exercise of this kind of talent in New York, where opposition to the decrees of the British Parliament, together with the popular local element of agitation, was in conflict with the staid laws of the Mother Country. Morris and Jay stood side by side in maintainance of the Colonial cause. Morris's skill in debate was of great value in the local gatherings. When the State was rapidly resolving itself into open revolt, in a speech of eloquence and sound logic he maintained and defended the independence of the American Colonies. Before this, and even during his minority, he had begun to take interest in public affairs. In consequence of the French and Indian wars, the Colony was in debt. A bill was before the New York Assembly to provide for this by raising money by the issue of interest-bearing bills of credit. Morris attacked this bill with great vehemence, opposing any issue of paper money which would, he argued, end in catastrophy and bankruptcy; but later on, as we shall see, he took a different view of this subject.

The Colonial Government of New York at this period was a sort of an aristocratic republic, its constitution similar to that of England. The power was vested in the hands of the wealthy land-holders, such as the Livingstons, Van Rensselaers, Schuylers, Van Cortlandts, Jays, Ludlows, Beekmans, Roosevelts, Morrises and others. For more than a century these magnates held political sway, save by contests between themselves, or with the royal Governor. Some of these rich landowners held black slaves, and lived in state and great comfort in roomy manor-houses with wainscotted walls, and enormous fireplaces, encompassed by well-kept gardens, intermingled by box hedges and formal-shaped flower beds. Certain representatives of these families remained loyal to England. Staats Long Morris, Gouverneur's elder brother, remained a royalist and rose to be a Major General in the British Army, and married the Duchess of Gordon.

The rebellious sentiment and opposition to the dictum of Great Britain in New York and New Jersey was somewhat behind the more radical leaders of New-England. Indeed, the battles of Lexington, Concord and even Bunker Hill, had been fought before the New Yorkers became thoroughly aroused. The sturdy men of New York, though slow at first, were far sighted enough to see the true value of the struggle and most of them joined the patriots. They were men of a high ideal of freedom, and too fond of liberty to be overtaxed and arbitrarily ruled by a nation three thousand miles away. Morris, who belonged to the ruling Episcopalian Church, was at first slow in siding with the patriots. The semi-secret society of the "Sons of Liberty" originating among the merchants, which at times took the form of mob-law, he disliked, and argued for compromise, but at length, when he saw no hope of reconciliation, and the British ministry growing more imperious, and the Colonies more defiant, he cast in his lot with the patriots. Once in, he was not the kind of a man to look back, or even waver.

Like the great Washington at this crisis, Morris fully believed that a lasting separation from the Mother Country was now inevitable. In April, 1775, the last Colonial legislature in New York adjourned for all time and in its place various committees were formed and met in convention to elect delegates to the Continental Congress, and also to the Provincial Congress, of which there were eighty-one delegates, including Gouverneur Morris from the County of Westchester. Morris said in 1776, "Experience will teach the British powers that an American war will be tedious, expensive, uncertain and ruinous." He said, "Why should we hesitate? Have you the least hope in treaty? Can you trust in the acts of Parliament? No, they come from the king. We have no business with the king. He has officially made himself a party in the dispute against us. Trust crocodiles, trust the hungry wolf in your flock, or a rattlesnake in your bosom. But trust the king, his ministers, or his commissioners is madness in the extreme." The war having fully commenced he wrote to his mother from the convention at Fishkill thus: "What may be the event of the present war it is not in man to determine, but he who dies in defence of the injured rights of mankind is happier than his conqueror or more beloved by mankind."

The constitution of New York, which was finally adopted, and which continued the basis of the law of the State till 1821, owed much to the labors of Morris. He was constantly employed in the various duties of semi-civil and semi-military character, in negotiations with the officers of the army, and visiting General Schuyler with whom he was in full sympathy. The following year the New York convention made him a member of the Congress at Philadelphia, and almost immediately he visited Washington at his camp at Valley Forge, where the General's half-starved and shoeless army were quartered. Morris took up his residence there for the winter. The intimate friendship formed with Washington and the influence of the latter helped Morris in his duties in the Congress at Philadelphia. The two years which he passed in Congress included the mission of Franklin to Paris. This called forth important services from Morris in the foreign negotiations leading to the treaty of peace. One of the first steps in this Congress was to provide means of raising funds. A committee was chosen, of which Morris was a member, and he prepared and drew up the report. It was found impossible to raise the amount needed by direct taxation. In his report in behalf of the committee he recommended an issue of paper money, that the Continental Congress should name the whole sum needed, and apportion the several shares to the different colonies, each being bound to discharge its own allotted part, and all together to be liable to whatever any allotted Colony was unable to pay. It must have been rather hard for Morris, a metal currency man, to have been obliged to acquiesce in the adoption of paper money. However, at this desperate state of affairs, it was a necessity, he plainly saw. This plan worked well at the time and strengthened the bond of union between the colonies. Morris's mind had now become thoroughly national, and his voice was often heard in Congress, being one of the leaders, and no doubt one of the best orators in that body. He took a conspicuous part in the religious controversey of the time also, but the limit of this paper forbids only a mere mention of this. When General Washington was on his way to take command of the army around Boston he passed through New York the same day royal Governor Tryon arrived by sea, and the authorities were in a quandary how to treat two such officials. Finally it was agreed to send a guard of honor to attend each. Montgomery and Morris, as delegates from the Assembly, received Washington, and brought him before that body, who addressed him cordially, but ended in this noteworthy phrase: "When the contest should be decided by an accommodation with the Mother Country, he should deliver up the important trust that had been confided to his hands." ' 'This,'' says one author, "gives us the key to the situation." Even the patriots of the Colony, at that time, could not realize that there was no hope of an "accommodation." Washington, the far-sighted statesman, urged the New Yorkers to take a bolder stand, and presently they did. As the Declaration of Independence had been ratified by most of the colonies, the State Constitution organized, and the die was cast. The third Provincial Congress of New York came together and before the close of its sessions, on account of marauding parties, was obliged to adjourn to White Plains, where they acted on the Declaration of Independence, and lay the foundation of a new State Government. Morris at this time was a zealous worker, and the acknowledged head of the patriotic party in New York. In one of his speeches he predicted that if we gained our liberties, "all nations would resort hither as an asylum from oppression." This has literally proved true, and, no doubt, to our great disadvantage, by the injudicious law of giving the vote to a vast multitude of persons without a property qualification. About this time the Provincial Congress changed its name to that of "The Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York." Just previous to this Morris had been sent to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia on complaint that the New England troops were paid more than those from other colonies. This Morris got remedied and returned to his own State in triumph after a week's absence.

The constitutional convention of New York led a checkered existence. The members, pursued by the victorious British from town to town, at times resolved themselves into a committee of safety with arms by their side in self-protection. The most important duties of this Convention were in charge of two committees. Of the first, was to draft a plan for the Constitution. Morris, Jay and Livingston were the three leading members. Of the second, was to devise means for the establishment of a State fund. Of this committee Morris was chairman. He was also chairman of a committee to look after the Tories, and prevent them from aiding the British. This was an unwelcome task, for many of his relatives, including his elder brother, were staunch Loyalists. The family mansion, where his mother lived, was within the British lines. About this time one of his sisters died, and in a letter to his mother were marks of deep feeling. The letter closes by sending love to "such as deserve it, the number," he adds, "are not great." Among the questions that came up in the Convention was the abolition of domestic slavery. Morris and Jay strenuously advocated this, but their fellow members in opposition outnumbered them, and the cause was postponed. As soon as the Constitution was adopted, a committee, headed by Morris, Jay and Livingston, was appointed to organize the new government. The courts of justice were formed and put in running order. A council of safety of fifteen members, Morris being one, was established to act as the provincial government until the new Legislature should convene. An election for Governor was held and George Clinton was chosen. At this juncture of affairs Burgoyne with his army was approaching from Canada through the northern part of the state, causing the wildest excitement. The council of safety was at its wit's end to know how to act, but finally sent a committee of two, Morris being one, to General Schuyler, the commander-in-chief. Morris outlined a plan for the army in part as follows: "Harass the British in every way without risking a stand-up fight and to lay waste the country through which the enemy were to pass so as to render it impossible for an army to subsist." You all know the story how the New England members of Congress, always jealous of New York, took advantage of General Schuyler's caution and had him replaced by Gates, who subsequently coveted Washington's position in the army. Morris was very angry at this treatment of Schuyler, but nevertheless did all in his power to strengthen Gates, and predicted his success. In a letter to Schuyler, dated September 18, 1777, Morris praised him for the way he behaved and roughly commented on Gates's littleness of spirit. It appears at first, the leaders in New England, like Samuel Adams and John Hancock, did noble service, but later on they hampered nearly as much as they helped the patriot cause. Morris stood by Washington nobly, and did him great service on nearly all of his measures he wanted put through; in fact, Washington chose Morris as his confidential agent to bring favorably before Congress a matter in which he did not consider politic to write about; viz., to stop giving admission to the service foreign officers who were clamoring to be appointed. General Lafayette and one or two others, of course, were an exception. In 1778 the British sent over commissioners, headed by Lord Carlisle, to treat with us. They had propositions called "Lord North conciliatory bills," two in number-the first giving up the right of taxation, the second authorizing the commissioners to treat with the revolted colonies in all questions of dispute. This was done in fear of an American alliance with France. Two days after the bills were received Morris drew up and presented his report, which was at once adopted by Congress. The tenor of this report was that the indispensable preliminaries to any treaty would have to be the withdrawal of all the British fleets and armies, and the acknowledgment of the independence of the colonial states. This decisive step was taken when the colonies were without any allies, but only a few days afterwards messengers came to Congress with copies of the treaty with France, which was immediately ratified. Again, Morris was appointed chairman of a committee to prepare an address on this subject to go before the American people.

Shortly afterwards he drew up, on behalf of Congress, a sketch of the proceedings of the British commissioners, under the title of "Observations on the American Revolution." He was one of the committee to receive M. Gerard, the new French minister, and upon this he was selected by Congress to draft the instructions to be sent to Franklin, the American minister at the French Court. Morris was instrumental in having the famous Thomas Paine removed from the secretaryship of the Committee of Foreign Affairs for his venomous attack on Silas Deane and the French Court.

He had to deal also with an irritating matter affecting the State of New York. This was the dispute about the boundary between the latter State and Vermont in which Clinton, the politician, took an active part. Regarding the western boundary of the State, Jay was for extending it as far west as possible. Morris, not so far sighted, did not agree with him, saying, "A territory we cannot occupy, a navigation we cannot enjoy, not worth quarrelling about." In 1779 Morris was defeated for Congress and about this time took up his abode in Philadelphia. In 1780 he published a series of Essays in the "Pennsylvania Packet" reviewing the state of the national finances, which gave proof of his ability in that line, and probably in consequence of this, through his friend and namesake, Robert Morris, received the appointment of his assistant, "Minister of Finance," at an annual salary of $1,850, which lasted three and one-quarter years. The report of 1782, to which Jefferson subsequently was indebted, formulating a decimal system of notation for the national coinage, was prepared by him.

Morris, good-looking, well dressed, a wit among men and a beau among the ladies, drove about the streets of Philadelphia in a phaeton with a pair of small spirited horses. One day his horses took fright, threw him out and broke his leg, the bone so badly shattered it had to be amputated, and ever after wore a wooden stick, as many of his pictures will show. This loss of limb did not prevent him from mixing in society, of which he was very fond. The death of Morris's mother in 1786 threw the family residence at Morrisania, which had been cut off by the enemy during the war, into the hands of his elder brother, a British officer residing abroad (already alluded to), from whom he now purchased the estate. Soon after peace was declared each colony set up for itself, and for four or five years had no settled policy or credit. We refused to pay our debts, or our army. Mob violence nourished, notably "Shays' Rebellion" in New England and the "Whiskey Insurrection" in western Pennsylvania. Our statesmen saw the absolute necessity of a National Union. Morris, then a delegate from Pennsylvania, was one of the great leaders of this movement, and made the final draft by his own pen of our Federal Constitution. Washington, Hamilton and Morris advocated a strong National Government. Patrick Henry and most of the Southern statesmen were zealous defenders of "States' Rights." Henry said in his Virginia speech, "The American spirit, assisted by the ropes and chains of consolidation, is about to convert this country into a powerful and mighty empire." Morris, to his credit, was not a full believer in free suffrage. He said, "to give votes to people who have no property, they will sell them to the rich." In pursuance of this theory, he brought forward a plan, the chief feature was for an aristocratic Senate, and a democratic House, which would hold each other in check. He wished to have the president hold office during good behavior. The year after these labors Morris gratified a long-cherished desire of visiting Europe, and after a stormy passage of forty days arrived in France, and reached Paris February 3, 1789, in time to study the opening scenes of the French Revolution. He remained there and in other parts of the Continent many years and kept a diary of the leading events. He found Jefferson installed as American Minister, planning and consulting in affairs, and was very handsomely received by Lafayette. Morris's aim was to study the character of the French, and he did so very closely. He was at once admitted to the highest social and political circles. Of Necker he says, after a glance at his counting-house manner and his embroidered velvet costume, "If he is really a very great man I am deceived." He disposes of Talleyrand, of whom he saw much, in a very few words. "Sly, cool, cunning, ambitious, malicious." On the fourth of July, 1789, dining with Jefferson and a large party of Americans, he urged Jefferson to persevere if possible in advocating some constitutional authority to the body of Nobles, as the only means of preserving the only liberty for the people of France, and soon after he gave the same advice to Lafayette, who appeared to be hostile to his ideas, and the Frenchman's wife still more so. Morris was always wont to freely give advice in all political matters. He was at the opening of the States General in May at Versailles, and the following July word was sent him that the Bastile had been taken. A few days later, walking in the Palais Royal, he saw the head of Minister Foulon on a pike, his body dragged naked on the earth. "Gracious God," he exclaimed, "what a people." April first of the following year Mirabeau died. Morris witnessed his funeral, which was attended by more than a hundred thousand persons. He says, "Vices both degrading and detestable marked this extraordinary being." In his studies of the French people he has left on record this: "There are men and women who are greatly and eminently virtuous, I have the pleasure to number many in my own acquaintances, but they stand forward from a background deeply and darkly shaded." In a letter to Washington he called the nation "a kind of political colic." While in Paris he corresponded with Paul Jones, aiding him to go into the Russian service, as he expected soon there would be warm work on the Baltic, and in the same letter advised him not to visit Paris. One of Morris's services to Washington was to procure him a gold watch. Washington's order was "not for a small, trifling, nor a finical, ornamental one, but a watch well executed in point of workmanship, large and flat, with a plain, handsome key." Morris purchased the watch with two copper keys, and one golden one, including a box containing a spare spring and glasses, and sent them to him by Jefferson.

Another service to the Father of his Country was this order, "Go to M. Houdon's (the sculptor), he has been waiting for me a long time." And Morris says, "I stand for the statue of General Washington, being a humble employment of a manikin." It is said that Morris resembled the great Virginian in looks more than any other American statesman of his time. Among the famous ladies of the salons where Morris often visited was Madame de Stael, who amused him, though in his diary he says that he never in his life saw such exuberant vanity as she displayed about her father Necker. Morris often met Madame de Flahaut at her salon. Once, when dining with Morris and Talleyrand, she told them in perfect good faith that if the latter was made minister "they must be sure to make a million for her." It was a coarse age. Morris says that he often met the fair sex at their toilets, but adds, "their operations at this task were carried on with an entire and astonishing regard to modesty." In the spring of 1790 Morris went to London, in obedience to a letter received from Washington appointing him private agent to the British Government, to see if he could induce them to strictly carry out the conditions of the treaty of peace previously made between Great Britain and the American colonies. Although Morris spent nearly a year in London he failed to accomplish anything. "The very name of America," said the king, "was hateful" to him. Here at home Morris's enemies blamed him for his failure there. They thought, and with more or less reason, that his haughty manner and proud bearing made him unpopular with the king and his minister. Probably a greater reason for his failure at the English Court was his intimacy with the French minister stationed there, M. de la Luzerne, and other French leaders whom the English disliked and were suspicious of. On leaving London he made a trip through the Netherlands, and up the Rhine. By the end of November we find him back again in Paris, but was soon called back to London, making a number of trips between there and Paris during the year 1901 looking after his own business affairs. At this time he might be properly called a speculator. He engaged in different schemes of a business nature, and is said to have made a great deal of money. He shipped tobacco from Virginia. He contracted to deliver Necker 20,000 bbls. of flour for the relief of Paris, wherein he lost heavily. Another of his projects was on behalf of a syndicate, where he endeavored to purchase the American debts to France, thinking they could be bought low and then get full pay in America, but I believe this project came to naught.

Morris was fond of the theatre, and enjoyed himself to the full, especially when in company of the Parisian ladies of quality. He thus describes one of the characters at the Opera: "One girl by the name of Sarenser, very handsome, but next door to an idiot as to her intelligence, appeared in a ballet in a dress, designed at her bidding, to be more indecent than nakedness."

The priesthood he very much disliked and kept clear of them. The great church leader Maury, Morris said looked "like a downright scoundrel." He drafted many papers for the French Ministry and one for the King which he liked, but his ministers prevented him from using it. In the spring of 1792 his credentials arrived as minister at the French Court. At the same time Washington sent him a word of warning, admonishing him not to let his brilliant imagination get the better of his cool judgment. Morris took the letter in good part and profited by it as far as lay in his nature. In the desperate state of affairs in Paris at this time, Morris had much sympathy for the King and Queen and tried to get them out of the city by a number of plans, but of no avail. One of the plans the King said he regretted his advice was not taken, and at the same time asked him if he would not take charge of the royal papers and money. Morris declined to take the papers, but consented to take charge of the money, amounting to about seven hundred and fifty thousand livres, which was paid out in living and bribing the men who stood in the way of the escape. The King remained in the city and the 10th of August the Swiss guard was slaughtered, and the whole scheme of escape at an end. The King on the scaffold prayed that his deluded people might be benefited by his death.

In 1796 Morris accounted for the expenditures to the dead King's daughter, and turned over to her the remainder, which was one hundred and forty-seven pounds. It appears that Morris was the only foreign minister who stayed in Paris during the reign of terror. It was an extremely dangerous position, but he faced the difficulties with unwonted courage. He wrote home that he could not tell "whether the King would live through the storm; for it blew hard." The horror of the mob was terrible. The shelter of Morris's house and flag was constantly sought. The old Count d'Estaing, and others of note who fought side by side with us in our war of independence, he sheltered in his own house. Morris said, "The vilest criminals swarmed in the streets, and amused themselves by tearing the earrings from women's ears and snatching away their watches." Morris befriended Lafayette out of his own purse, when in prison and in want; besides he had the sum of ten thousand florins forwarded to the prisoner by the United States banker at Amsterdam. He gave the Duke of Orleans, afterwards King Louis Philippe, money to flee to America, and the debt was not paid till after the death of Morris, which amounted to about $14,000. It needed no small amount of courage of Morris's avowed sentiments to stay in Paris and do what he did when death was mowing round him in such a wide swath. Many times his life was threatened, and more than once he said it was only saved by the fact of his having a wooden leg which made him known to the mob as "a cripple of the American war for freedom."

Thomas Paine, the Englishman, who was there and had been elected to the convention, having sided with Gironda was thrown into prison by the Jacobins. He at once asked Morris to demand his release as an American citizen, a title to which he, of course, had no claim. Morris refused, thinking Paine by keeping still would be saved by his own insignificance. So "the filthy little atheist," as one called him, had to remain in prison, where he amused himself by writing a pamphlet against Jesus Christ.

Much more might be said of Morris while in Paris, but time will not permit. The French rather took umbrage at

his haughtiness, but Washington, on the whole, approved of his conduct. The insulting aggressions of the French minister Genet at home now compelled the United States to ask for his recall.

In August, 1794, Monroe was selected to take the place of Morris at the French Court, although Washington's first choice for the position was Thomas Pinckney, whom he would have transferred from England to France. Roosevelt says that "Monroe entered upon his new duties in Paris with an immense flourish." Meanwhile Morris did not return to America. On account of his business affairs in Europe he prolonged his stay abroad for several years, visited Switzerland, stopping a day with Madame de Stael at Coppet, then toured through England, Scotland, the Netherlands, Germany, Russia and Austria, and interested himself in the liberation of Lafayette, then in prison at Olmutz. He was received everywhere into the most distinguished society of the time. At length Morris wound up his business transactions in Europe and sailed from Hamburg Oct. 4, 1798, reaching New York after a tedious passage of eighty days, and immediately joined with the Federalist party, although during the year 1799 did not take much part in politics, but occupied most of his time in putting to rights his estate at Morrisania. The old manor-house, a leaky affair, he tore down and built a large, solid and comfortable one in its place. The next year he entered into law practice and met such legal lights as Hamilton, Burr, Robert Livingston, Troup and others. In 1800 we find him engaged in an important law-suit before the Court of Errors at Albany, in which he had Hamilton for his antagonist, and the same year he was selected by the legislature to supply a vacancy in the Senate of the United States, where he became a staunch pillar of Federalism, retiring at the close of 1803. The next year called him to utter his lamentations at the bier of his friend Hamilton, which John Randolph declared "was a wretched attempt at oratory." During Morris's absence of ten years, the control of the National Government had been in the hands of the leaders of the Federal party. Their great support had been Washington, aided by Hamilton and others. Washington's death in 1799 greatly diminished the success of that party. Jefferson was the great leader of the opposite faction-the Republicans- which was gaining a great foothold in governmental affairs.

Virginia, the great political battle ground, had lost Washington, the wisest statesman of all time. Also Patrick Henry, the great orator; but Marshall and Madison were left to battle for Federalism aided now by Morris of New York and a few others. Morris wrote from Washington to one of his lady correspondents in Paris at this time, describing the seat of the American Government. He said that the city "needed nothing but houses, cellars, kitchens, well-informed men, amiable women, and other little trifles of the kind to make the city perfect." He thought Jefferson a tricky theorist, skillful in getting votes, "a man who believed in the wisdom of mobs, and the moderation of Jacobins." Morris, as a rule upheld the administration of President Adams.

In the purchase of Louisiana Morris broke with his party and voted with the Republicans. Almost his last speech in Congress was a telling one in favor of at once occupying the territory in dispute. The cost of the purchase of Louisiana he brushed aside. He said "a counting-house policy which saw nothing but money, a poor, short-sighted, half-witted, mean and miserable thing, as far removed from wisdom as a monkey from a man."

At last Napoleon, in great need of funds, sold us Louisiana for $15,000,000. Morris said, "I am content to pay my share to deprive foreigners of all pretext for entering our interior country; if nothing else were gained by the treaty, that alone would satisfy me." Morris's term as senator expired March 4, 1803. The State then being Democratic he was not re-elected, but continued to be interested in public affairs. He was one of the leaders in studying the prospect of the Erie Canal; in fact, the project was advocated by him during the Revolutionary War. The three first reports of the commissioners were all from his pen. "Stephen Van Rensselaer, one of the commissioners from the beginning," said Morris, "was the father of our great Canal." From this time on he spent most of his time at Morrisania, travelling two or three months every summer, out in the "Far West," on the shores of Lakes Erie and Ontario, and once descending the river St. Lawrence. He tilled his farm, and was otherwise occupied in reading and receiving his friends. He also carried on a wide correspondence on business and politics. On the 25th of December, 1809, Morris, then 57 years old, married Miss Anne Gary Randolph, a member of the famous Virginia family of that name. He lived happily with her and had one son.

Morris was rather formal in his manner of living, dressed himself with great care and was very particular about his powdered hair. He took the greatest pleasure in life, and always insisted that America was the pleasantest country in which to live. He was somewhat erratic in his opinions. He considered the policy of Jefferson during his second term of the presidency, also Madison's, as pitiably weak, so much so, it exasperated him and really made him lose his head. He almost lost faith in our republican system. His former interest in the West now revived, and he proposed that our enormous masses of new territory "should be governed as provinces and allowed no voice in our councils," an absurd idea put forth in his declining years. Morris's bitterness, late in life, against the government grew strong, and finally his hatred really got the better of his former and sounder judgment. He opposed the various embargo acts and nearly all other government measures. His opposition to the late war with England led him to great lengths. In his bitter hatred of the opposite party, he lost all loyalty to the nation. He approved of the peace on the terms the British offered, which included the curtailment of our western frontier and the creation along it of independent Indian sovereignties under British protection. He argued with Pinckney that it was impious to raise taxes for an urgent war. He tried to induce Rufus King, then in the Senate from his own State, to advocate the refusal of supplies of every sort, whether of men or money, for carrying on the war, but King did not obey him. Morris wrote a letter to Harrison Gray Otis, a secession sympathizer, saying that he wished the New York Federalists to declare publicly that the Union, being the means of freedom, should be prized as such, but that the end should not be sacrificed to the means. He wrote to Pinckney Oct. 17, 1814: "I hear every day professions of attachment to the Union. I should like," he writes, "to meet with some one who can tell me what has become of the Union, in what it consists, and to what useful purpose it endures." He actually regarded dissolution of the Union as almost an accomplished fact, and that New York would go with New England, and it was a quandary in his mind whether the boundary should be the Delaware, the Susquehanna, or the Potomac. He hoped and expected much of the Hartford Convention by way of secession, and he wrote to Otis that the Convention should declare that the Union was already broken and that they should take action for the preservation of the Northwest. He was disappointed when the Convention fell under the control of Cabot and the Moderates. As late as January 10, 1815, he wrote that his section would be benefited only by the severance of the Union. It is impossible to reconcile his course at this time with his previous career. Morris was not alone in advocating secession of New York and New England; with him were Harrison Gray Otis, Samuel Dexter, William Prescott, Elijah H. Mills, Israel Thorndike, Benjamin Russell, John Wells, Pinckney, Quincy, Lowell, and even Daniel Webster, who was accused by Theodore Lyman as a disunionist. A stenuous politician of our day says that "Morris's place is alongside of men like Madison, Samuel Adams and Patrick Henry, who did the nation great service at times, but each of whom, at some one or two critical junctures, ranged himself with the forces of disorder."

Fortunately, this nation in its infancy brought forth a statesman who above all others of his time was pre-eminent for his steadfast devotion to liberty and the welfare of all the people, a wise and far-sighted official, the immortal Washington. After the peace with Great Britain in the 1812 War, Morris accommodated himself to the changed condition with apparent cheerfulness. He good-humoredly yielded to the inevitable, and in his very last days said, "Let us forget party and think of our country. What does it signify whether those who operate her salvation wear a Federal or Democratic cloak?" On his death-bed he said: "Sixty-five years ago it pleased the Almighty to call me into existence here, on this spot, in this very room; and shall I complain that He is pleased to call me hence?" On the day of his death he asked about the weather. Being told it was fine, he replied (his mind recurring to Gray's "Elegy"): "A beautiful day; yes, but

‘Who to dumb forgetfulness a prey,

This pleasing, anxious being ere resigned,

Left the warm precincts of the cheerful day,

Nor cast one longing, lingering look behind?’ "

This pleasing, anxious being ere resigned,

Left the warm precincts of the cheerful day,

Nor cast one longing, lingering look behind?’ "

After a short illness of the gout he died November 6, 1816, and was buried on his own estate at Morrisania. He was a brilliant man, a good orator, and had a very keen intellect. He was truthful, upright and fearless, but was haughty in his manner and possessed a tyrannical quality in his disposition, which at times led him into trouble with his fellow-men. He was exceedingly generous, hospitable, and extremely fond of good living. Witty and humorous as a companion, but of rather hasty temper, he had many good qualities and some faults.

The late Mr. Moore, formerly librarian of the New York Historical Society, put on record the following: "Gouverneur Morris of New York, one of the noblest of her sons, a great man and a good citizen, who could truly say that the welfare of his country was his single object- during a conspicuous career. He never sought, refused, nor resigned an office, although there was no department of government in which he was not called to act; and it was the unvarying principle of his life that the interest of his country must be preferred to every other interest. Such a man was Gouverneur Morris, the inspired penman of the Federal Constitution."

The country, certainly, owes much to him for his good services and brilliant statesmanship. He was the author of "Observations on the American Revolution" (1779); "An Address to the Assembly of Pennsylvania on the Abolition of the Bank of North America" (1785); "An Address in Celebration of the Deliverence of Europe from the Yoke of Military Despotism" (1814); an inaugural disccourse before the New York Historical Society on his appointment as its president, and funeral orations on Washington, Hamilton and Gov. George Clinton. He also, late in life, contributed political satires in prose and verse to the newspaper press.

It is generally admitted that he was the more far-seeing observer of contemporary men and events than any other American or foreign statesman of his time, and his colloquial powers were unrivalled.

It is to be regretted, however, that in his last days, when virtually in retirement, he should lose his head, so to speak, by going back on his former political teachings and theory of government and allying himself with a small coterie of prominent New England men who were apparently advocates of secession. As a consolation to his friends and adherents of our day, the same might be said of many able statesmen who have lived in the States since his time, who committed the overt act of secession, and seemingly without permanent harm to themselves or the cause they represented. If in your judgment my mind is out of gear in making this statement, or if I thus predict too prematurely, I await for some future historian to confirm or deny this declaration of mine.